The State of Data at SatSummit 2024

I was honored to provide an opening presentation on “The State of Data” at SatSummit yesterday. While I didn’t read this speech verbatim, this is the text I prepared for the presentation along with my slides.

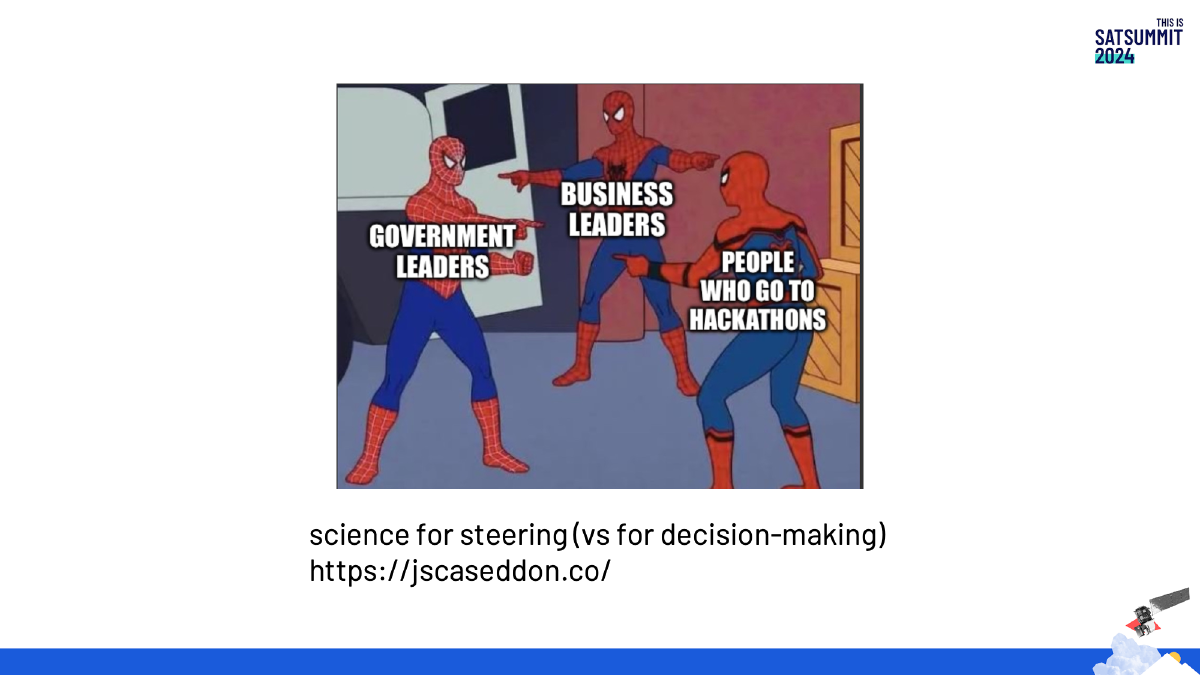

The most consistent feedback I got from the presentation was people’s appreciation for Jessica Seddon’s idea of “imaginary decision-makers” which I took from her blog post titled science for steering (vs for decision-making). Many thanks, as always, to Jessica for being a great thought partner.

And many many thanks to the entire SatSummit team for putting on such a wonderful event. I can’t say enough good things about it, and my only complaint is that it gathers so many thoughtful people that it’s impossible to get enough time with them in such a short time. I’m on my way home lamenting all of the conversations I wasn’t able to have.

We have a motto/framework that guides what we do at Radiant. It’s More data, more available, to more people. That’s what we’re trying to make happen, and I’m going to use this framework to explain how we see the state of data today.

So, first of all: more data. This actually isn’t something we’re worried about.

You may have heard of “surveillance capitalism” or the “military-industrial complex.” I imagine fewer of you have ever heard of the term MICIMATT, which stands for Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-Media-Academia-Think-Tank complex.

No matter how these terms make you feel, they point to an interesting phenomenon, which is that we have an extremely robust economy that relentlessly produces data about our world. It’s kind of amazing if you think about it.

A lot of the great stuff we’ll be talking about here is possible because we’re drafting off of advances made by these complexes.

I’m not trying to make any claims about whether this is good or bad. I’m just saying that the creation of data isn’t something we’re worried about. I mean, heck! The “great debate” at this event is whether or not the “humanitarian community should own and operate its own satellites.” Imagine traveling back to 2015 and proposing such a thing at the first SatSummit. It would have been ludicrous.

So, moving on. Are we making data more available?

The good news is that making data available is a mostly solved problem from a technology standpoint. There are some macro trends to thank for this.

- Cloud computing has become commoditized. Generic plain cloud storage has proven to be good enough to host data at just about any scale. This is great! Competition and commoditization among cloud providers give us low costs, great performance, and a very large ecosystem of tools to work with.

- Along the same lines, we now have nonproprietary highly efficient file formats that take advantage of the cloud. One of our main initiatives at Radiant Earth is the Cloud-Native Geospatial Foundation which aims to help more people benefit from this fact. Please go check out guide.cloudnativegeo.org which was produced by our beloved friends at Development Seed and NASA to get an idea of what’s possible. If you want to make data available, you can get very far today by simply putting files and metadata into the cloud.

- Compute and open source tools just keep getting better! We now have very powerful tools that can work with monstrous amounts of data. One thing I’m particularly excited about is that browsers are becoming incredibly powerful data interaction and analysis tools. There’s a session this afternoon called Data in the Browser that will blow your mind. Making data in browsers has a powerfully democratizing impact because browsers are a very widely distributed tool – particularly in low- and middle-income countries. One crazy bonus macro thing going on right now is that large language models have dramatically lowered the cost of producing code, so we can expect more and better tools to keep coming.

All of this combines to make the plain old World Wide Web an extremely capable platform for EO data.

So, are we satisfied? Absolutely not. Here’s the bad news.

First, the cloud is still too hard to use. For very legitimate cultural, legal, or procurement-related reasons, simply “putting files on the cloud” isn’t an option for many organizations. Our other big initiative at Radiant is called Source Cooperative, which aims to make it much easier for people to publish data in the cloud.

But that’s just for publishing “finished” data products that have already been processed and are ready for others to use. Actually processing data at scale in the cloud is also still really hard. Fortunately, we have a lot of very talented people building startups to solve this problem such as Earthmover, Wherobots, and Fused.

Second, even if we make the cloud easy, we have a lot of work to do to make data more interoperable. We’re confident that more earth observing satellites are going to keep coming, but we still don’t have widespread agreement on which discrete global grid systems we should all use.

We also need to start using common data schemas and identifiers to refer to the things we care about on the planet. We aren’t going to be able to cooperate on global issues if we can’t agree on how to refer to things.

We’re currently working with the Taylor Geospatial Engine to develop a common schema for agricultural field boundary data and we’ve been funded by AWS to do the same for air quality data. Other good work happening in this space are Overture Maps’ Global Entity Reference System, OpenSupplyHub’s work to standardize supply chain data, and Varda’s work to create unique identifiers for farm fields.

But these challenges pale in comparison to the third, far greater, challenge: We still don’t know how data functions as a market good.

Many of us in the open data world have spent a long time in a paradox: we know that data is valuable and we also believe much of it should be free.

Designing, building, and launching satellites costs money! Storing and transferring data costs money! This is hard work!

These aren’t controversial statements! But it feels right that earth observation data should be widely available. Make no mistake: I like “free” data, by which I mean to say that I am happy to know that my tax dollars subsidize open access to a lot of great data products. We all benefit by pitching in to make a lot of data available at no cost.

I also believe that we’d benefit from having a well functioning market for all the data that the government won’t or can’t make available for free. I believe that much more data would be available to us if we could figure out how to price it appropriately.

Unfortunately, any normal economic analysis of this is warped by the fact that the satellite sector is heavily subsidized by the Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-Media-Academia-Think-Tank complex.

We still don’t know if we should be selling pixels, files, APIs, platforms, or applications. But don’t be sad. This is a brand new sector. What we’re doing is profoundly novel and it’s ok that no one has figured it out.

A big part of our work at Radiant is to support and collaborate with people who are exploring alternative business and funding structures to make markets for data work. I’m proud that Radiant is a supporter of PLACE’s work to create a mapping data trust. And we’re proud to be the fiscal sponsor of Clay, which is moving very quickly to figure out a sustainable way to help people benefit from open Earth observation foundation models.

We need more people experimenting with business models!

So, that’s a lot of work to do, but here’s the even harder part: more people.

I’m just going to read this passage from my great friend Jessica Seddon:

I keep running into imaginary decision-makers. Some person, or an organization that behaves like a person, who will look at the evidence and then … do the right thing. Do the evidence-based thing for the societal good.

Be on the lookout for imaginary decision-makers throughout your conversations here. It’s very easy for us to be entranced by data and forgetting that our work isn’t just about data, but about the outcomes we hope to achieve with the data.

If we want data to be used for the public interest, we need to face the fact that many humans and institutions don’t change their behavior simply based on data! Decision making is very complex and simply having access to a beautiful map or dashboard is not going to save us from ourselves. We need to transcend the map and be more serious about distilling Earth science data into the systems where decisions are made.

The “more people” part of our framework is there because I’m convinced that we’ll be better off with larger and more diverse community of people who can work with Earth science data. But we know that’s not enough.

We need to also make sure these people have power to use the data in service of the public interest. The way to help most people is to use data to inform better governance and service delivery.

This means we should be unafraid to try to create new institutions that are truly data driven and held accountable based on data. We have a panel about this after lunch too.

So! In conclusion:

- Cloud-native works! It helps us move faster and reach more people. Join us!

- Let’s get to work creating common data schemas and identifiers. This is critical work that has been overlooked for way too long.

- We can’t kick the can down the road hoping that people in power will act on data merely if we make it available. Let’s be bold and transform existing institutions and create new ones.

If we don’t figure this out, making more data more available to more people is going to be about as effective as pushing a rope.

What a time to be alive. This is hard stuff, but it’s really important, and it’s possible. And look around! We’re so lucky to get to be together to work on these things!